CHISELED: on Madonna and the Marbles (**nudity and sexual imagery**)

- Ben

- Aug 22, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 2, 2025

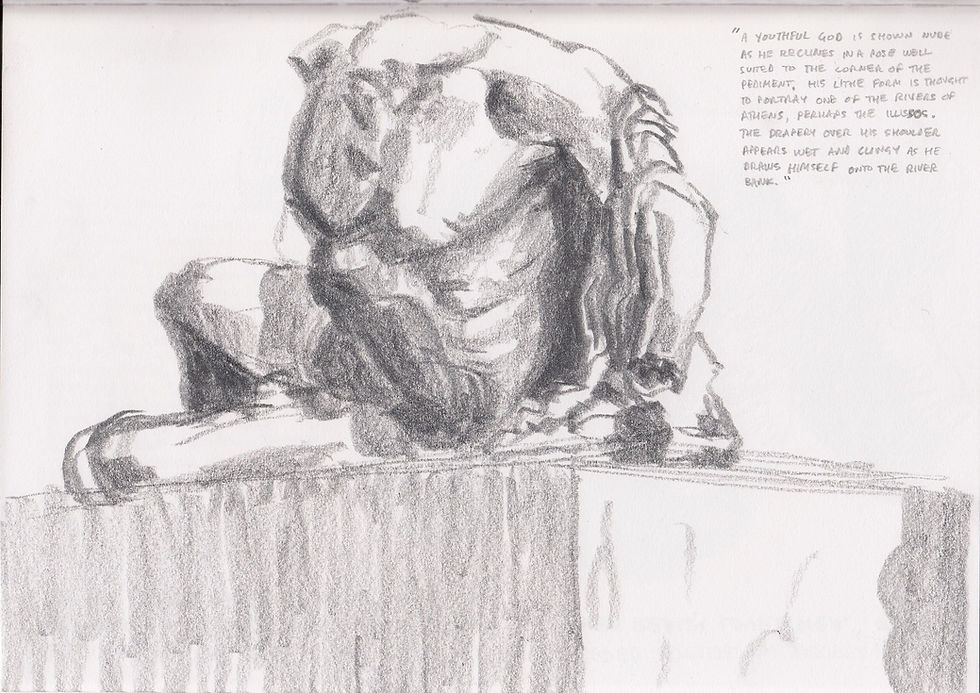

This year is the 30th anniversary of Madonna's photo-book Sex. I was an adolescent when it was published but I clearly remember a conversation between some critics on the radio at the time. One of them said Madonna's boobs were 'lower' than they'd expected: the intimation being that her body was somehow not as 'good' as they had anticipated. Another said "It's like she can't get naked enough," suggesting, as I understood it, that the images came across as effortful in a way that was unfortunate; that Madonna's nudity betrayed a kind of desperation - no matter how naked she was, it wasn't enough for her. They were talking as though Madonna had done something that made her look foolish. Their words surfaced in my mind earlier this year as I sat drawing the Parthenon Marbles in the Duveen Gallery at the British Museum. Clad in many layers against the wintry draft that came through the gallery's open doors, I felt my body was the opposite of the ones I was drawing. I couldn't wear enough clothes. They couldn't get naked enough. I had chosen to be here as a participant of the Royal Drawing School's Drawing at the British Museum course*, partly because of an idea that these ancient Greek stones would help me think about bodies and about the ideas that shape them.

It has been said that Madonna's book upset the mainstream critical community because of its counter-cultural agenda; depicting assertive female nudity, gay sex and androgynous bodies. The Parthenon Marbles, by contrast, are said to tell a story that was very much in line with the agenda set by Athens' most powerful citizens. As Mary Beard describes in her book How Do We Look, Athens was a "city of images", filled with depictions of the human body that reinforced a culture both "deeply gendered, and rigidly hierarchical."

Where Madonna's images blur categories, the Marbles are insistent about sexual dimorphism: male bodies are hard and highly toned, often held in postures of conflict that heighten these characteristics, while female bodies are curved in shape and looser in pose. Another contrast between Madonna's pictures and the Parthenon Marbles concerns who gets to be naked and how. In Sex, everyone shows their body with apparent confidence. In the Marbles, females are almost always at least semi-clad in drapery, as with Amphitrite (consort and charioteer of Poseidon) and Iris (the messenger goddess):

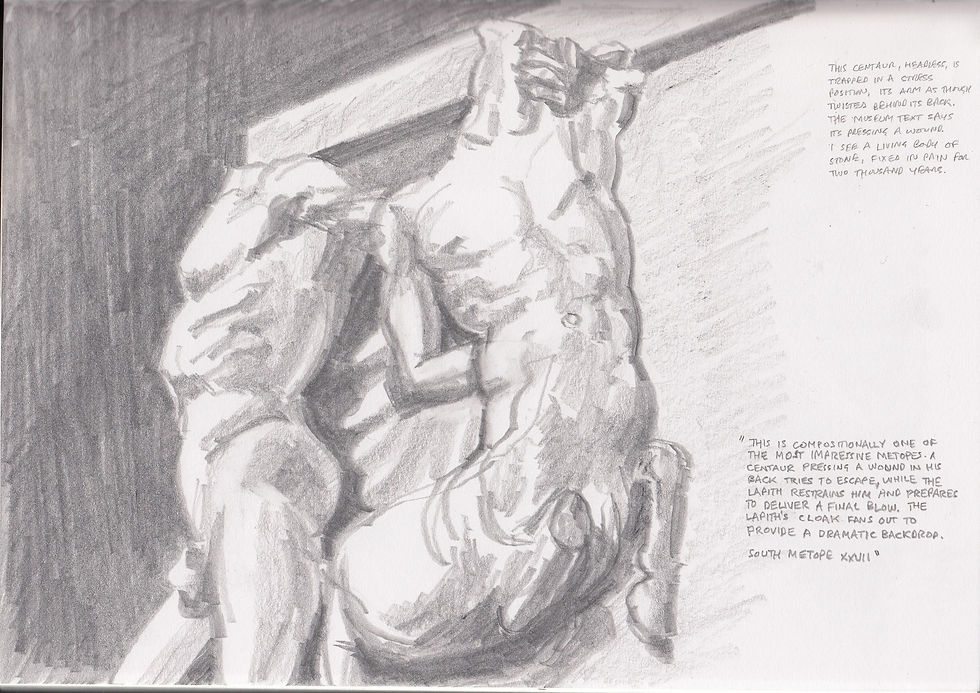

The male bodies, meanwhile, are extra-naked, all but stripped of their flesh. They were made, I think, for a viewer who wanted to penetrate the form with their gaze, who wanted to look at anatomy so distinct as to create a kind of sympathetic pain, a tingle in the fingers. This is the pre-modern expression of the fantasy of X-ray specs.

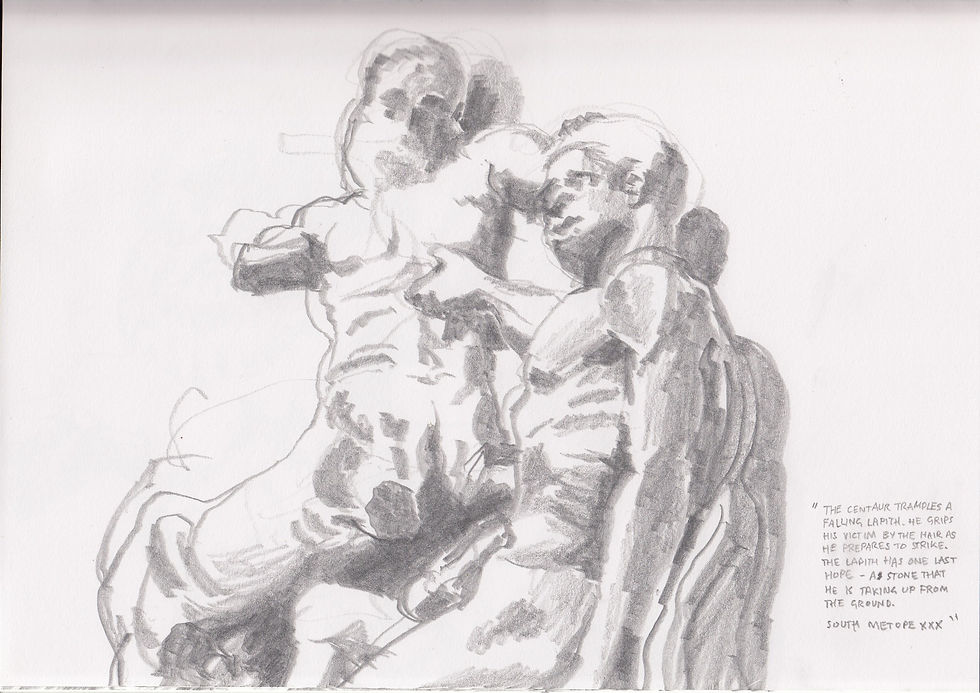

Many of these are bodies held in what today might be called 'stress positions': arms twisted behind torsos, heads wrenched on necks, hair gripped in fists: positions, I became aware with a disturbing feeling, that have now been held for centuries.

For all their apparent 'realism', these depictions have little-or-nothing to do with real bodies. Their purpose was to bring into being a set of ideals based on race, beauty, civilisation, power and gender hierarchy. Men were strong and hot while women were defined, as much as anything, by what they lacked. In this famous depiction of the Crouching Venus (one of the few female nudes on display in this part of the museum), the goddess tries to conceal herself from an intruder:

Mary Beard says these images are comparable in purpose to western advertisements of the second half of the 20th century. “This was no crude campaign in social instruction," she writes, "but taken together they were telling the Athenians how to be Athenian.” Further, she says, it was this ancient Greek imagery, spread in particular through the distribution of decorative pottery, "that made a particular form of the human body ubiquitous [...] throughout the western world, and more widely." When the collectors of the Victorian era moved the stones to London, they applied a further dose of X-ray vision, heightening the already exaggerated anatomy by scrubbing away remnants of the original paintwork that gave them skin tones and brightly coloured accessories. This move also had the benefit of increasing the stones' whiteness - a quality the Ancient Greeks didn't seem to have valued but which the British collectors obviously did (inspired in part by the earlier classical revival that took place during the Rennaisance). Many of us are still toiling under some version of this same high-contrast bodily ideal, as a quick browse of the internet might confirm.

The satisfaction comes from the way Madonna seems to be channeling James Dean as much or more than she is Marilyn Monroe

It's interesting to compare the images in Madonna's book with what's visible in the British Museum's ancient Greece collection. Some of the group photos involve arrangements that could easily fit in among the Parthenon's battle scenes. In a 2017 article for Rolling Stone, Barry Walters described how, with the benefit of distance, the section of the book in which Madonna "sandwiches herself between hip-hop’s Big Daddy Kane and supermodel Naomi Campbell is more stilted than ever."

There is something in these pictures that reminds me very much of the rigidity and rhythm of formal Athenian pottery.

(Credit: British Museum)

(Credit: Matthias Kabel)

(Credit: MR via pinterest)

In a review for the New York Times written the year Sex was published, Vicki Goldberg suggested Kane's facial expression was due to a feeling that he was at "the wrong party". I can read his expression as one of awkwardness. But I can also read it as one of concentration - revealing his commitment to getting the scene right. The photographs aren't sexy to me, but neither are the pots.

Maybe what Madonna succeeds most at with these pictures, perhaps what she's thought her best thoughts about, is the throwing off of classical gender separations. First of all, she and the other women involved are as confidently naked as the men - often more so (see Big Daddy's briefs). But maybe more important is what Madonna does with her naked body. How she wears it. My favourite photo is the one in which she poses as a hitch-hiker on a highway, a cigarette dangling from her lips, her thumb wagging at the passing cars.

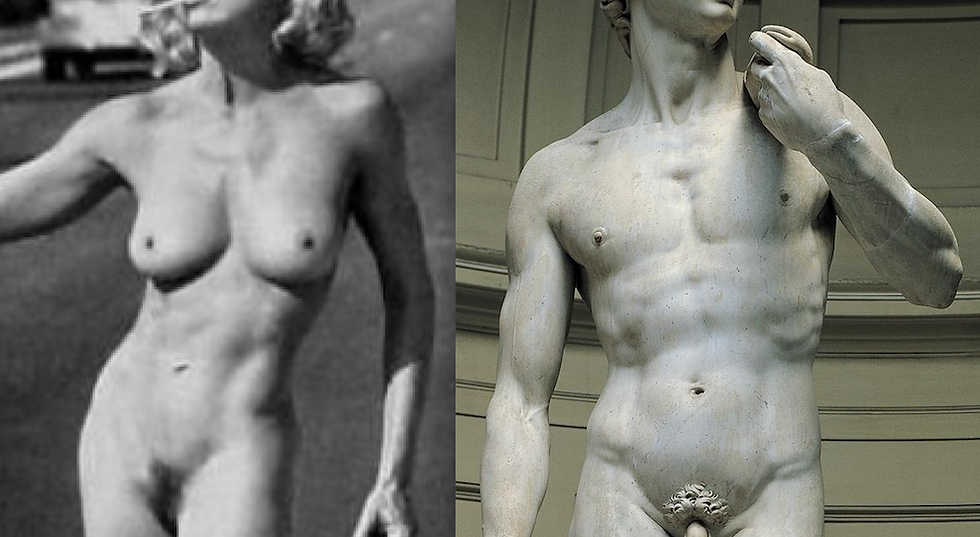

The satisfaction comes from the way Madonna seems to be channeling James Dean as much or more than Marilyn Monroe. Despite the obviously 'feminine' features of her body, what Madonna is borrowing most heavily from is her culture's tradition of masculine beauty. The way she holds herself is totally in keeping with the male strand of the Greek sculptural tradition: the deliberate de-centring of the hips and subtle tightening of the abdomen; the squaring of the shoulders; the vein-popping grip of the left hand; the toe-pointing of the loosened foremost leg; the way the lighting picks out the snaking contours of her lower ribs and abdomen. All I can see is Greek marbles.

Maybe the comparison is even closer when we look at the Renaissance version of the classical body. Here's Madonna next to Michelangelo's David (photo credit Everett Collection):

Historically, the meaning attributed to depictions of bodies has been highly gendered, with images of male nudity often drawing negative reactions while female nakedness is accepted as safe. According to art historian Eva Kernbauer, "male nudity was closely linked to strength, invulnerability and heroism," while "depictions of female chastity and female nudity are historically deeply interlinked. The female nude is not threatening at all - female nudity is vulnerable, because it acknowledges the gaze of the beholder."

In Sex, Madonna rejects the submissiveness her culture expects of her and instead steals the beauty and danger claimed by men. But where does this leave us if, on some level, this stolen beauty is synonymous with a tradition we want to question, or even relinquish? As Isabella Rossellini put it in a 2014 interview about the project, the perfection Madonna's body brought with it was, for her, an unhappy influence.

"If you see a businessman - or me, an older woman - naked, there is a vulnerability. I thought that the book lacked that. Madonna was almost too beautiful, too perfect ... too shaped, to have that vulnerability or the sense of shock that a regular, more normal, not so professional fitted body, could convey."

It's a great description. Professional fitted body. As though a sculptor has been brought in to shape Madonna's person to the image of beauty in her mind. Having now - for the first time - looked at Sex in its entirety, I have mixed feelings about the comments of those critics I heard speaking about it when I was young. There's plainly nothing 'low' about Madonna's boobs or anything otherwise imperfect about her body. She does an excellent job of measuring up to the marbles she is mimicking. But what about the other criticism? Does she get naked enough? I don't know. She seems at least as naked, as chiseled, as some of the bodies of the Parthenon. This is part of her success as a thief of beauty, a thief of power; and of her success as a maker of queer culture. But in another sense - the one Rossellini is referring to - both she and the marbles fail at nudity: because they fail at humanity. It makes me wonder what the book would have been like if Rossellini had been in charge. It makes me wonder what our depiction of bodies would be like - and how we might feel and think differently about our bodies - if vulnerability and strength weren't so polarised and so gendered. It makes me wonder what it might feel like to live outside these images that spread from Athens more than two thousands years ago and have remained ubiquitous ever since.

Post Moikios (23rd August 2022): a friend this morning introduced me to the term ‘contrapposto’, an art-historical term describing the off-centre posture used for standing figures in Classical Greek sculpture and by Madonna in her hitchhiking photo. According to Wikipedia, contraposto “was historically an important sculptural development, for its appearance marks the first time in Western art that the human body is used to express a more relaxed psychological disposition.” It can “encompass the tension as a figure changes from resting on a given leg to walking or running upon it…” and “creates the illusion of past and future movement.” So Madonna is claiming not just beauty and power but relaxation and dynamism too. Which makes sense.

All photos from Sex are copyright © Madonna forever and ever.

*Kindly funded by Arts Council England through a Developing Your Creative Practice grant. Thanks you, ACE!

I appreciate your observation that Madonna was recapturing James Dean's poses and attitudes. Now that I've seen it, I can't avoid seeing it.

It annoys me a bit that people would look at a naked woman and complain that she fails at her nudity because her breasts are too low or because 'she doesn't look like me'. That wasn't her job. Her job was to look like Madonna and express Madonna's attitude. I think it was a complete success.

I guess I am about the same age as you, Ben, but I find it interesting that I deliberately avoided looking at Madonna's Sex when it came out because I didn't want to be the kind of person who looks at…