ROCKS THAT LOOK LIKE MEAT: on Muscular Christianity

- Ben

- Aug 29, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 2, 2025

During the 1980s, when I was something less than ten years old, my brother and I auditioned for roles in a stage adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s Junglebook. Despite the fact that, as far as I could tell, I was the better actor, my brother was cast in the lead role of Mowgli while I was given a non-speaking role as one of a chorus of monkeys. I understood that my brother seemed more wild. He had a restless energy that he found hard to disguise, he was more energetic, less self-contained than I was. Perhaps the people running the show had gathered something of this and felt it fitting for the lead role. I also recognised that his body was different to mine. You could see his ribs more clearly. His nipples were smaller. I wondered if Mowgli had small nipples. I contemplated the possibility that my brother had been cast as Mowgli because he had an outie. Knowing that my brother was faster, more athletic, more physically confident than I was, I had long ago created a superstitious association between these qualities and the fact that his bellybutton was not a hole like mine. It seemed quite possible that a boy raised in the wild - a boy required to swing from trees and speak the language of panthers - would also have an outie.

Both of us were required be to be topless during the performance. On the night of the show, I remember a small group of children coming up to me during the interval and looking on as one of their number, wearing a slow grin, addressed me with a question: 'Male or female?' Reflecting on the event now it occurs to me that maybe this person was attracted to me, that their behaviour was a form of 'negging' provoked by a desire to control my prettiness, but at the time I understood their words as intended to humiliate me. I felt that my body was being impugned for its failure to meet expectations. I was being asked to clarify something, to pick a side, to account for my failings, to gender myself. It struck me a little later that perhaps this - my body's seeming ambiguity - was also something to do with the casting. Was Mowgli a boy or a girl? Were they boyish? Feminine? Manly?

Around the same time I was coming under criticism from the males in my life for being 'too sensitive'; for being 'fastidious'. In school PE lessons I was told I needed to 'toughen up'. I was told I was 'getting fat' by several family members. (I was in love with Harrison Ford - for the fact that he was the opposite of me in these respects; for the seemingly arbitrariness of his anger and the surprise it provoked in him; for the autism and unavailability he maintained - a glamorous archetype for what I found in my fathers; and for the beautiful, tree-like immutability of his body). A few years later, as an adolescent, I grew taller than average but became slender with it. I was now 'too thin'. I watched my elder brother lifting weights, cultivating a muscular, defined torso. There are photographs of him from this time, looking handsome with his shirt off. A class-mate at A-level college referred to me as 'girl-boy'. Later this same class-mate came to school complaining of pain in his abdomen, caused by his own attempts to do sit-ups, as part of a plan to address what he saw as a problematically flabby belly.

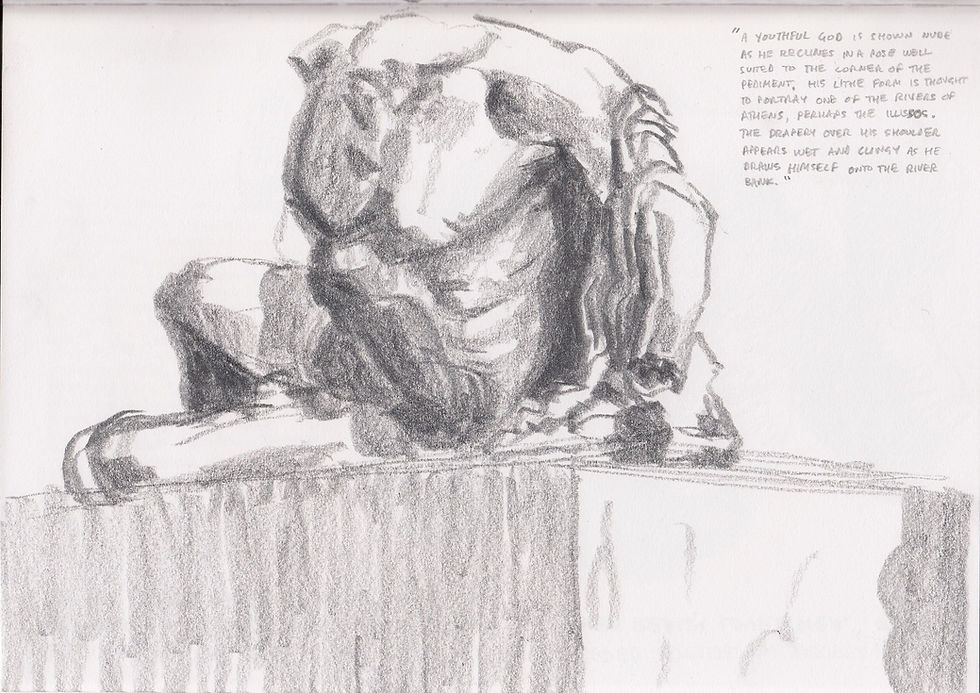

A superficial glance at instagram, or at the images dominating our TVs and cinemas, will tell you that ideas about what constitute 'good' and 'bad' bodies still capture a lot of attention. Recent developments in the worlds of fashion and advertising have seen a greater variety of bodies being used to sell things but images of ideal and highly gendered bodies still surround us much of the time: slender-tender / muscular-hard. Dating from Classical Greece, these body-images are touch-stones, sources of psychic energy; they are the point of origin of the images that fill our minds of when we think about what it means to be 'Western', to be European, to be 'white', or to be gendered. And the amazing thing is that the original images from which these ideas were drawn still exist, embodied in the stones housed in Greek and Roman rooms at the British Museum.

It's no coincidence that the Parthenon marbles were brought to the UK during the period of peak British imperialism. The importation was funded and led by people who were profiting from the Empire and harboured a strong desire to identify with Classical precedents. The British Museum is itself a monument to the Victorian obsession with Athenian culture. Its facade, added in the 1850s, is based on the temple of Athena Polias at Priene, and includes 44 Ionic columns and a mock-Greek pediment depicting the progress of human- (or, to be precise, man-) kind. Racialised questions of progress and purity were a preoccupation in 19th century Europe and America, especially among the most powerful. Many public figures were self-declared eugenicists and there was wide-spread fretting about 'racial decline' - prompted perhaps by the fear of losing the hegemony that had been gained.

As in ancient Athens, writers and artists favoured by the centres of power were working hard on mythologies that promoted and justified the status quo. In the USA, the essayist and preacher Ralph Waldo Emerson was conjuring stories about the ruggedness and self-reliance of the 'perfect man', setting this in opposition to the 'sensuality and sloth' of 'degenerate effeminacy'. In the UK, the novelist Charles Kingsley was more explicitly concerned with bodily form. In his 1874 book Health and Education, he wrote about the value of Greek statues as 'heirlooms of the human race', of their "tender grandeur, their chaste healthfulness, their unconscious, because perfect, might." The statues were, he said, tokens "of what man could be once; of what he can be again if he will obey those laws of nature which are the voice of God."

I suppose you will all allow that the Greeks were, as far as we know, the most beautiful race which the world ever saw. Every educated man knows that they were also the cleverest of all races; and, next to his Bible, thanks God for Greek literature.

- Charles Kingsley, Health and Education, 1874

But the Victorian vision of ancient Greece was premised as much on fantasy as it was on research. After importing the marbles, the new owners made significant alterations in line with what they wanted Athenian culture to represent, including an imagined alignment with their own values. First, they mounted them at floor level, presenting them as educational - even instructional - objects intended for close viewing (unlike on the original Parthenon where they were many meters above ground). Second, they heightened the already-exaggerated anatomy by scrubbing away remnants of the original paintwork that gave the statues an array of skin tones and brightly coloured accessories, even pubic hair. This move also had the benefit of increasing the stones' whiteness - a quality the Ancient Greeks don't seem to have valued but which the British collectors and conservators definitely did.

One outcome of collecting things for display is that you then have to make decisions about whether and how these things are grouped together. At the British museum, objects are gathered in such a way that they reflect ideas of ethnicity, history and geography and in a way that reinforces a separation between 'peoples'. If you walk out of the western-most parts of the British Museum, across the Great Court and up a flight of stairs, you will find yourself amongst collections of bodily images from multiple times and places, presented in such a way as to propose an association. I'm not clear what I think about this. But moving from the Parthenon to the South-East Asian rooms in a single day, I am struck by certain contrasts: sexual dimorphism and tension seem to feature less prominently in the latter; neither chiselled abs nor stress positions are present.

I have an impulse to describe these bodies as 'androgynous', as though this were a category of exception. But, really, on these terms, 'androgynous' is a much more truthful description of the bodies of most of the people I know, the bodies of most of the people I see swimming at my local pool. They are like my own body, the body whose bellybutton turned in, that was queried by that other child in that auditorium during the intermission at that performance of the Jungle Book thirty-odd years ago. It makes me want to track the history of androgyny as an idea - and its links to colonialism. What am I really seeing when I look at all these bodies?

It's likely that Rudyard Kipling, the author of the Jungle Book, would have seen the Parthenon marbles during his time in London during the late 19th century. Growing up between England and India, he became almost the paradigmatic British colonial story-teller. I wonder now how he pictured the body of Mowgli. How he pictured his own body, how he understood himself as a body and how that understanding was shaped by his colonial upbringing. Would he have predicted the fact that his story would eventually appear on cinema screens? That it would be adapted into plays in which white English children were cast in the leading roles?

The British Museum's website states that "successive Greek governments have refused to acknowledge the Trustees' title to the Parthenon Sculptures" but that "there are no current discussions with the Greek Government on this issue." Their claim on the stones seems to rest on its self-conferred status as a 'world museum' and on the outcome of an investigation conducted by a British Parliamentary Select Committee in 1816, which concluded that the acquisition of the Marbles had been 'entirely legal'.

We know that the marbles mean something different in their current context at the museum than they did in their original setting, 2,400 years ago, or than they might if they were moved to another place today. The thought of moving them feels exciting to me. I'm curious to know what it would do to them. It also makes me want to ask what it would do to the experience of visiting the British Museum if the stones were given back and, say, replaced with plaster casts or 3D printed copies. What's the worst case scenario? As a visitor, I'm fairly sure I would still gain a great deal from looking at them. And maybe, on the up side, if the British Museum took the decision to deliberately let go of the Marbles, to participate in their re-framing, their re-materialising, it would be a step towards loosening the grip maintained by the traditions they represent for Britain: of stoniness, of acquisition, of unrealism, and of the mind captivated by whiteness.

Comments